I absolutely despise thinking about damnation. The concept, it seems to me, is often used in a less than charitable and prudent way. Nonetheless, because I am writing a book on salvation, I'm forced to now think through issues relating to it.

I've been carefully re-reading Hans Urs van Balthasar and Karl Rahner. I'm naturally inclined to their more optimistic view of salvation--wouldn't it be nice if in the end most if not all were saved?

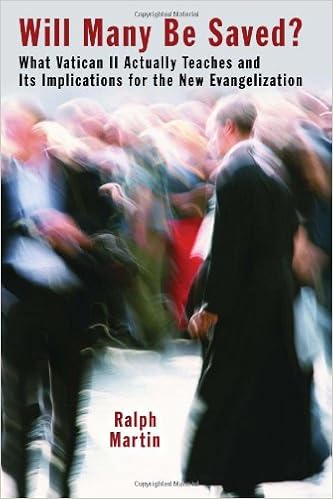

Yet I'm now reading through Ralph Martin's Will Many Be Saved?: What Vatican II Actually Teaches and Its Implications for the New Evangelization (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2012).

I was particularly struck by this section of Martin's critique of Rahner.

"Apart from the scriptural and magisterial witness to the contrary, even from an empirical point of view it is difficult to understand Rahner's optimistic view of human beings' response to what he postulates as the supernatural existential. He acknowledges that's optimistic theory of the 'positive response rate' of human beings needs to be tested against empirical observation of actual human beings and what we can observe of their response. The puzzling empirical fact is that he spent virtually his whole priesthood (1932-1984) first under Nazi rule and then, after World War II, with half of Germany under Soviet communism. He published his first major works in 1939 and 1941. He spent the whole of World War II in Nazi Germany and Nazi occupied Austria, free to lecture although not at a university. From 1939 to 1944 he lectured in Leipzig, Dresden, Strasbourg, and Cologne, laying the theological groundwork for his theories. Consider the slaughter of so many tens of millions--including the firebombing of Dresden; the horrifying realities of the campaign to exterminate the Jews and the millions of concentration camp deaths--including those of many Polish Catholics; the fiendish medical experimentation. Did this not give pause to his theory that almost everybody says 'yes' to the offer of salvation contained in the 'supernatural existential' apart from any hearing of the gospel? Is it at all credible to posit that the grace of God has 'overtaken' the 'false choices' of men in these and many other empirically observable situations?" (p. 103)

Indeed, the more I think about it, it does seem that many Catholic thinkers of the twentieth century failed to come to terms with the truly horrifying reality of the holocaust. It is surprising to see how little it actually is accounted for in much modern theology. It is affirmed, yes. I'm

certainly not implying people like Rahner are holocaust deniers. The issue is deeper. What real impact did it make on his

thought? In the case of Rahner's rather optimistic view of humanity, that does seem to be a valid question.